Reconstruction 8.3 (2008)

Return to Contents»

Screenplay Visualization: Concepts and Practice / Stewart McKie

Abstract: A typical feature film screenplay goes through many development iterations before the original story idea becomes the audio-visual movie we experience. As the screenplay is developed it becomes more complex and may involve an ever-larger group of "content stakeholders" who have a need for different perspectives on the content of the screenplay. Here I discuss four conceptual archetypes for analyzing and visualizing the textual content of a screenplay: Circular, linear, rollercoaster and nodal. I show examples of support for screenplay analysis and visualization in the current generation of screenwriting software and I also suggest how these visualizations and others may provide insight into ways to improve the quality of a screenplay.

1. Introduction

<1> A typical feature film screenplay generally begins life as an idea in a writer's head (i.e. a "spec" script) or as an idea commissioned by a buyer (i.e. a script commission). At this stage it is far from what is often characterized as a "plan" or "blueprint" for a movie. Initially, what could eventually become a substantial piece of content of some 90-120 A4 pages may begin life as a much shorter description of the story idea in the form of a story synopsis or "treatment" often used to pitch the story idea. As the screenplay is formally developed by the writer (or writing team) it is populated with a cast of characters who take action and speak dialog as they participate in main or sub-plots that thread through a story organized into some kind of narrative structure - whether linear or non-linear in sequence.

<2> If a screenplay goes into development (usually after it has been optioned or bought) and then if it goes into production, it will involve a larger "content stakeholder" group beyond the original author(s). In development the screenplay may engage producers, directors and actors, in production it will engage set designers, prop managers and other crew functions and at various times it may also engage co-writers, studio readers, story analysts and dialog polishers, among others. Often, these content stakeholders are only interested in a very specific aspect of a script – the locations or dialog say – rather than the script as a whole.

<3> As the screenplay idea develops through revisions and rewrites, the content and context "bulk" of the story becomes more complex and layered. Over time it becomes more difficult – even for the original author(s) – to keep track of key elements of a screenplay such as the structural balance of the content, the development of the characters and the continuity of the plotlines. At some point it becomes useful for the content stakeholders to have access to different ways of reading and viewing the screenplay other than only by re-reading the text itself or viewing storyboards that link sketches, diagrams or photographs to specific moments (e.g. scenes or beats) in the script.

<4> What is needed to assist these content stakeholders are additional means of analyzing and visualizing all or some of the textual content to provide alternative ways of understanding and gaining insight from the text. In other words "big picture" overviews or "drilled-down" detail-views of this content that help content stakeholders to consider the text from different perspectives and perspectives that are intentionally designed to meet their specific needs. This is the aspect of screenplay analysis and visualization discussed here.

2. Analysis and Visualization Archetypes

<5> A review of screenwriting literature - texts about screenwriting by screenwriters, screenwriting teachers and industry "gurus" - indicates that there are at least four analysis and visualization archetypes that many screenwriters and screenwriting teachers or gurus already recognize. I term these four archetypes: Circular, Linear, Nodal and Rollercoaster. Examples of each archetype are referenced and briefly explained below.

2.1 Circular Archetype

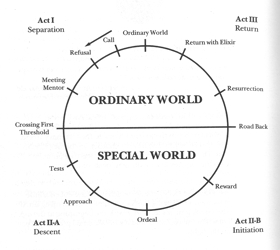

<6> The circular archetype is exemplified by Vogler's Hero's Journey [1] and Murdock's Heroine's Journey [2] paradigms as visualized in figure 1. This archetype is a character-centric and structural visualization of the screenplay content. It is character-centric because it is usually focused on the screenplay's protagonist (the "hero"/"heroine") and traces the character's physical, emotional and psychological "journey" via a series of clearly defined stages (Acts) and steps (Sequences of scenes with a thematic focus). It is structural, because the character's journey traverses two "worlds", progresses through 4 stages and navigates all (or most) of a number of named steps. Act 1 locates the character in their ordinary world from which they are "separated". Act II-A and Act-II-B details the character's "Descent" and "Initiation" into the Special World. Act III is concerned with the character's "return" to their ordinary world.

Figure 1. Vogler's The Hero's Journey [1:194]

<7> This archetype is termed "circular" because the journey begins in the "ordinary world" of the character, progresses through the "special world" the character comes to be involved in and returns the character back to the ordinary world – usually changed in some recognizable way.

2.2 Linear Archetype

<8> Probably the most famous example of the linear archetype in the screenwriting world is Field's 3-Act structure [3:21], an adaptation and application of Aristotle's concept of "Completeness" – "A whole is that which has a beginning, a middle and an end." [4:13] Field's structural innovation was to reframe this concept in screenwriting terms (see figure 2). The beginning becomes Act 1 that describes the "Set-Up" of the story and occupies some 30 pages/30 minutes of screenplay content/screentime. The middle becomes Act II concerned with the "Confrontation"(s) of the story, occupying some 60 pages/60 minutes of screenplay content/screentime. The end becomes the "Resolution" of the story, some 30 pages/30 minutes of screenplay content/screentime.

<9> Most screenplays are based on either a linear or non-linear narrative (i.e. sequence of story events) and in either case can be visualized using a linear archetype, which often references a baseline that represents the prospective movie timeline (i.e. the projected running time of the movie in minutes) or a list of sequential scenes in the screenplay. The linear archetype is usually used to analyze the progression of story elements over time, such as character or plot "throughlines", in the context of the division of the screenplay into clearly defined structural entities that encapsulate each other including: Acts, sequences, scenes and beats or shots.

Figure

2. Field's 3-Act Structure [3:21]

(Click image for larger version)

2.3 Rollercoaster Archetype

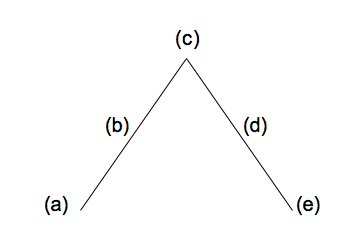

<10> The Rollercoaster or "mountain" archetype is derived from one of the earliest examples of dramatic analysis, namely Freytag's "pyramid" [5:115] that visualized what he termed the five parts of the drama - (a)introduction, (b) rise, (c) climax, (d) return or fall, (e) catastrophe) - and the three crisis points between these parts (see figure 3). The rollercoaster archetype is concerned with visualizing a number of aspects of a screenplay including escalating tension punctuated by "peaks and troughs" and the accumulating body of the story "bulk" as the screenplay progresses. Conventionally, tension escalates until the "climax" somewhere near the end of the screenplay. However, the build up to this climax is also punctuated by various emotional or psychological highs and lows to ensure the audience remains engaged with the story. But the rollercoaster archetype can also be used to visualize other variations in the overall "rhythm" of the screenplay to depict contrasts, say, between noise and silence, action and dialog, colour or other tonal aspects.

Figure 3. Freytag's Pyramid [4:115]

<11> The highs and lows are usually located with reference to a structural paradigm, such as Kenning's use of Field's 3-Act structure in figure 4, or against a scene or sequence-based timeline. Cooper [6] discusses many potential instances of the rollercoaster archetype to demonstrate how the climax can appear towards the beginning, middle or end of a screenplay depending on the effect the screenwriter is trying to achieve in their narrative choices.

Figure 4. Kenning's 3-Act Rollercoaster [7:94]

2.4 Nodal Archetype

<12> The nodal archetype is a more recent phenomenon, perhaps because it reflects the ability of computer software to quickly generate node-based visualizations from data input. In a screenplay context, an individual "node" could be used to represent a screenplay entity such as a scene or character and collections of linked nodes to visualize the relationships between these entities. Therefore nodal visualizations can be used for various purposes including structural visualization or to visualize character relationships (as discussed in section 3 below).

Figure 5. Kitchen's Structural Nodes [8:301]

<13> Figure 5 shows how a nodal analysis can be used to visualize the content of a screenplay by representing the whole script deconstructed as a series of (3) acts that use 13 sequences to organize 48 scenes. This kind of visualization does a reasonable job of presenting both the forest and the trees of a screenplay's content organization and is leveraged by many screenwriting software programs as a means to both to outline and navigate screenplay content.

3. Software Visualizations

<14> Although more or less screenplay analysis and visualization is provided by many of the leading screenwriting software packages, this capability is relatively new and under represented in current screenwriting applications. In this section I will discuss visualizations available today that can help writers to plan their screenplay and to analyze initial drafts to help make qualitative improvements to the content.

3.1 Story-Planning Visualizations

<15> Story-planning is an important phase of the screenwriting process and is primarily focused on imagining and developing the "world" of the screenplay, the "flow" of the story narrative and the "roles" of the various characters who populate the story world and participate in or generate the narrative flow. There are at least three visualizations that can help with this planning phase: Hierarchy or "tree" outlines, index cards and mindmaps.

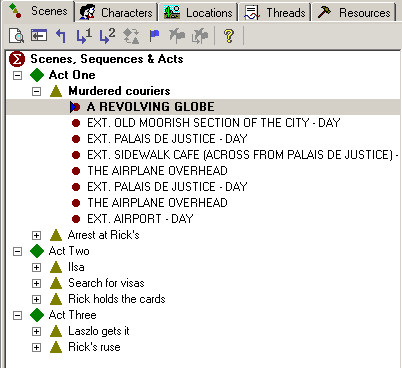

<16> A highly disciplined writer may begin planning their screenplay by envisioning it as a series of Acts, made up from Sequences, comprising individual Scenes representing a succession of story-Beats or camera Shots. Each of these entities can be summarized in the form of headings in a hierarchy outline before any detailed writing takes place to "fill-out" each heading. A number of screenwriting packages and specialized outlining tools provide this kind of outline (see figure 6).

Figure 6. An Outline in Sophocles

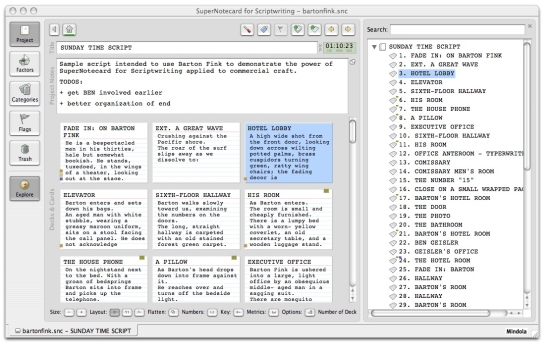

<17> Before the use of screenwriting software offered an alternative, writers used 3x5 cardboard index cards to plan their stories. These cards could be pinned to a corkboard and easily moved around to re-organize the main story points if necessary. Different coloured cards could be used to represent scenes within a specific plotline or scenes involving a particular character throughline for example. Most of today's screenwriting software (see figure 7) supports the visualization of a screenplay in the form of a series of "electronic cards" that can be moved around on-screen using drag-and-drop, and colour-coded and printed if required.

Figure

7. Index Cards in SuperNotecard

(Click image for larger version)

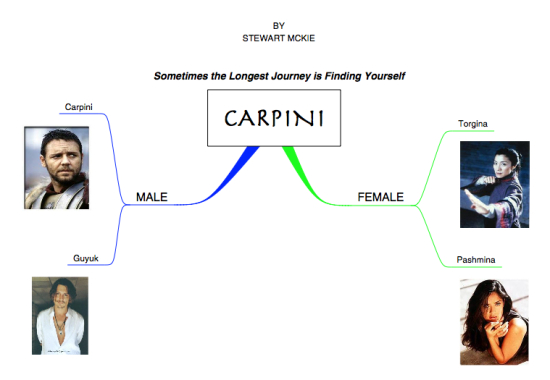

<18> Tony Buzan's mindmapping is a well-established technique for visually depicting an idea by connecting a central "trunk" idea subject or topic to multiple idea branches or sub-topics. A mindmap is a useful way to present a whole screenplay idea that might include characters, locations, scenes etc. all within a single map or to break the idea down into sub-maps, such as a map showing photos of the potential casting of characters (see figure 8) or a map of locations comprising evocative location shots. Mindmaps created with mindmapping software can include not just text and the link lines but also live links to web and other file content, visual images, post-it notes and playable video/audio content to help create a "rich-picture" of the scope of the screenplay idea. These visual "moviemaps" could be used to help develop and deliver a pitch as a means of marketing a screenplay to interested parties.

Figure

8. A Screenplay Casting Mindmap

(Click image for larger version)

3.2 Screenplay Draft Visualizations

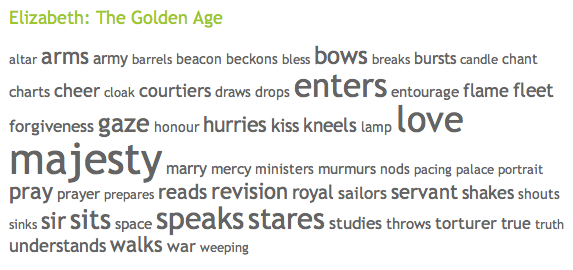

<19> All of the planning tools outlined above could also be used to visualize the content of the first drafts of a script, as well as the initial outline. But once there is a substantial body of content, there are other ways to visualize the body of text using software. To get some idea of the linguistic footprint of the script you could create a "scriptcloud" – a content cloud that visualizes the most frequently used or top-n words from the screenplay (excluding a "blacklist" of common "noise" words). The cloud could use the whole script as input or sub-sections from it – such as all the dialog or scene description text – to create multiple variant scriptclouds from the same core screenplay.

Figure 9. Scriptcloud of Elizabeth: The Golden Age

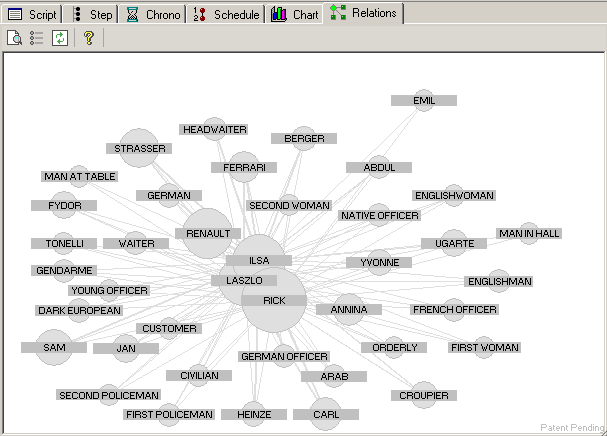

<20> Once there are multiple characters taking part in the action and speaking the dialog in a script, it may be interesting to see the relative "size" of each part and the relationships between the characters. A visualization of the "social network" of the script is one way to view this (see figure 10). Each circular node represents a character in the script and the lines their links to other characters. A larger node implies a larger part and more lines emanating from the node, a richer relationship profile for the character. Therefore one would expect the protagonist and/or antagonist to have the largest nodes and the most links.

Figure 10. A Casablanca Social Network from Sophocles

<21> It can be helpful for a screenwriter to view an entire script against a timeline axis to see as much as possible of the content and structural context of a script in one place. This helps to understand the balance of the script content, whether specific sections are too long or too short in terms of the potential movie screentime and to see the flow of acts/sequences/plots through the use of colour-coded sections. This visualization is provided by the StoryView package and can be printed out, poster-size for display on a wall (see figure 11).

Figure 11. A StoryView script poster

4. Screenplay Pre-Visualizations

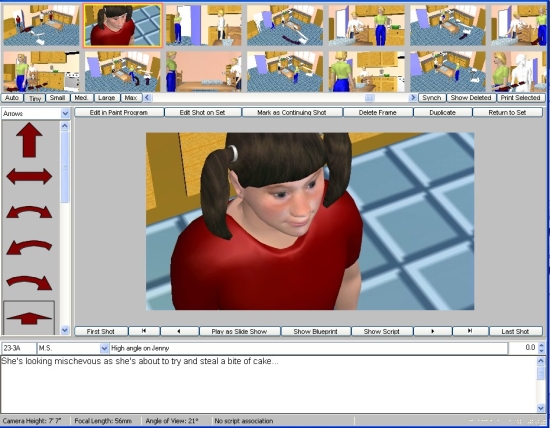

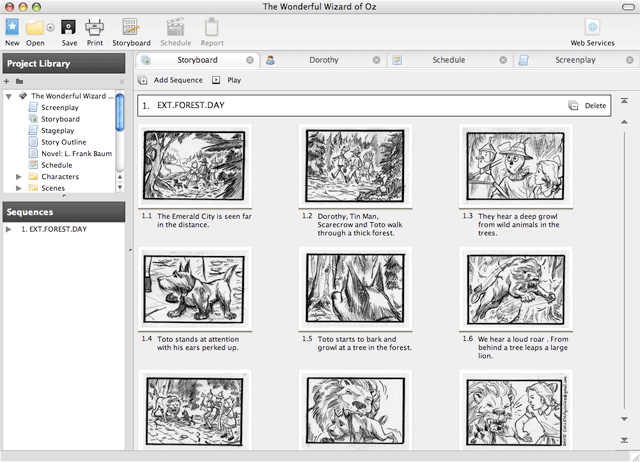

<22> Pre-Visualization or "previz" is the term used to refer to a preview of a visualization of the movie, prior to any actual filming taking place. Here I'll refer to two types of previz: Static and Dynamic. A static previz takes the form of a storyboard and a dynamic previz uses animation software to provide an interactive preview of what a shot (or series of shots) in a scene might look like. A storyboard artist usually draws each individual board by hand, although in storyboarding software a board can present any kind of digital image e.g. a photo of a location or person, whether originally drawn by a storyboard artist or not. One of the screenwriting packages providing the ability to link a storyboard to the script text is Celtx. In this case each board is an image that is "pasted" onto the digital board in the correct sequence to reflect the narrative flow of the screenplay content it is linked to.

Figure 12. A Wizard of Oz storyboard in Celtx

<23> A dynamic three-dimensional (3D) previz is computer-generated, sometimes directly from the screenplay text when it can be used as an input file, and depends on a toolbox of visual objects to construct the visual look and feel depicted. For example, the current version of FrameForge 3D (see figure 13) includes a library of over 800 posable actors and objects. Actors and objects can be adjusted and viewed from different points-of-view (camera angles). The individual previz shots generated can also be linked together so that a shot-by-shot slideshow can be created for playing online. This kind of previz is particularly useful for planning shots, confirming the right point-of-view is being used or simply understanding if a scene including a particular set of characters and/or props makes production sense.

Figure

13. A FrameForge

3D

posable actor figure

(Click image for larger version)

6. Future

Development

<24> There a number of visualizations not specifically intended for screenplay analysis that could nevertheless be used for this purpose. For example, Jeff Clark's Neoformix site includes four visualizations that could be used to analyze and visualize screenplays. His topic flower can help to visualize the emotional "tone" of a screenplay; his arc diagram can indicate links between scenes with similar linguistic content within a single screenplay draft; his shared word diagram used to compare and contrast two different screenplays, or prequel and sequel screenplays or two drafts of the same screenplay.

<25> Here I have focused primarily on screenplay analysis and visualization that is of benefit to the writer(s) of a screenplay. But other kinds of analytics with different goals are also possible. Predictive analytics applied to a screenplay may help studios and production companies to estimate the potential commercial viability and box-office success of a movie, as discussed by Gladwell [9] and Eliashberg et al [10]. Text analytics applied to a corpus of screenplays, versus an individual screenplay, may be helpful in genre analysis, for example to determine whether a new script obeys or subverts genre conventions when compared to an existing genre-archetype.

7. Conclusion

<26> Screenplay analytics and visualization offers many interesting opportunities for evaluating and improving the quality of a script. Although few screenwriting packages deliver much in the way of analysis and visualization, this is clearly an area of functional improvement for the future. There are also many kinds of visualization being applied to other kinds of data that could equally well be applied to screenplays, indicating plenty of scope for new insights to be generated that can help both the creators of screenplays i.e. the writer(s) and the consumers of screenplays i.e. studios and production companies.

Acknowledgements

Adam Ganz, Dept. of Media Arts, Royal Holloway.

Chirag Mehta (http://chir.ag/phernalia/preztags/)

Works Cited

[1] Vogler, Christopher. The Writer's Journey. 2nd Rev. Ed. London: Pan, 1999. [^]

[2] Murdock, Maureen. The Heroine's Journey. Boston: Shambhala, 1990. [^]

[3] Field, Syd. Screenplay The Foundations of Screenwriting. 4th Rev. Ed. New York: Dell, 2005. [^]

[4] Aristotle. Poetics. London: Penguin, 1996 (Trans. Malcolm Heath). [^]

[5] Freytag, Gustav. Technique of the Drama. Amsterdam: Fredonia Books, 2005 (originally published 1899). [^]

[6] Cooper, Dona. Writing Great Screenplays for Film and TV. 2nd Ed. Lawrenceville, NJ: ARCO, 1997. [^]

[7] Kenning, Jennifer. How to Be Your Own Script Doctor. New York: Continuum, 2006. [^]

[8] Kitchen, Jeff. Writing a Great Movie. New York: Lone Eagle Publishing, 2006. [^]

[9] Gladwell, Malcolm, "The Formula". The New Yorker, October 10 2006. March 16 2008. <http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2006/10/16/061016fa_fact6> [^]

[10] Eliashberg, Joshua, Sam K. Hui, John Z. Zhang. From Storyline to Box Office: A New Approach for Green Lighting Movie Scripts. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2006 (Revised: August 18). March 16 2008. <http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/papers/1329.pdf> [^]

Software References

Celtx <http://www.Celtx.com>FrameForge 3D <http://www.Frameforge3d.com>

Neoformix <http://www.Neoformix.com>

Scriptcloud <http://www.Scriptcloud.com>

Sophocles <http://www.Sophocles.net>

StoryView <http://www.Write-bros.com>

SuperNoteCard <http://www.Mindola.com>

Return to Top»